In 2011, David Coil posted about one of our most utilized mobile built environments-the cars we drive every day (or maybe not, if we adhere to an environmentally friendly lifestyle). A small study had just come out, in which the authors had attempted to identify the bacteria and molds present in cars in different climates. As David pointed out, the study was limited (see his original post here) due to its culture-based premise, though it did highlight an exciting new frontier in the world of built environment research. The ribosomal RNA survey that David called for three years ago (though it may not be exactly what he had in mind) is finally here, in a study published in the journal Biofouling: “Elucidation of bacteria found in car interiors and strategies to reduce the presence of potential pathogens.”

Using culture-dependent methods, the authors tested 18 cars from the Ford Motor Company employee vehicle fleet and found that the most highly bacterially colonized locations in these cars were the steering wheel, gear shifter, door handles, window switches and center console near the beverage holder. Using culture-independent methods on five of the 18 vehicles, the bacterial communities were found to consist mainly of Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus; unsurprising given their frequent contact with human skin. Streptococcus and Acinetobacter were also found in almost all locations sampled, along with a spattering of other bacterial genera found in just a few sampled locations.

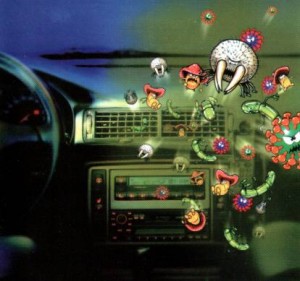

A cursory google search for “bacteria in cars” yields plenty of information about the “bad” bacteria and fungi in cars, particularly air conditioning systems, and how to remove these dangerous germs that are out to get us every time we get in our vehicles. The current article appears to take the same bent, focusing on Staphylococcus aureus while determining antibiotic resistance and testing a method for eliminating S. aureus from vehicle surfaces (coating surface with silver ion).

Lets consider a few things. First, the relative abundance of Staphylococcus species found in the 18 Ford Motor Company vehicles ranged from 1.05% to 77.1% (average about 28%). Additionally, only 31% of these Staphylococcus species were identified as S. aureus (the most abundant Staphylococcus species was, unsurprisingly, S. epidermidis). Therefore, I think it’s safe to say that how much S. aureus is found in cars can vary widely and even be non-significant, and I’m willing to bet that other environments that we spend time in (our homes, offices, etc.) affect us, and subsequently our vehicles, more than the other way around.

The authors did not test the antibiotic resistance of S. aureus in the Ford Motor Company cars, but moved to community-shared cars, discovering that nearly a quarter of S. aureus isolates from these cars were methicillin resistant. Before you think twice about renting a car again, have no fear-most of these methicillin resistant species were sensitive to tetracycline and all were sensitive to gentamicin, rifampin, and vancomycin.

In all, I like the premise of this study, and while the authors have proven that cars, especially community shared cars, can harbor methicillin resistant S. aureus, I feel that right now, other vehicles on the road pose more of a threat to our health and well-being than our own do.

Did they say why they tested Ford motor cars in particular? Or was it just that they are from Michigan?

Ah, good point. I’m assuming it’s just because they are located in Michigan. They also don’t explain why they begin by testing FMC cars and then move to rental cars. I assumed they wanted the community variable when testing rental cars, but why not do the entire study on the rental cars?

Not all DNA that is detected is viable. S. aureus survives max. few months on dry surfaces. Luckily enough, there is a lot of dead stuff around us.

Yes, very good point! In this study, the did use a mixture of culture-dependent and independent methods, so they were able to grow Staph aureus isolates from cars and test their antibiotic resistant. But I love what you bring up, because now we can say, of the avg. 22% of bacterial DNA that was considered to be Staphylococcus, and of the 31% of that 22% that was actually aureus…how much represented live bacteria vs. DNA that had just been hanging around for awhile?

Would it make any differences in the study on the bacteria in the heating systems? I see the air conditioning system is mentioned and, of course, heat would make some difference, I suppose.

It might, actually, make a difference. I was hoping that the authors would have tested the A/C systems, too. I also wish they would have focused more on describing the entire microbial community that they found, as opposed to just focusing on the potential pathogen.