Anyone considering the possibility of welcoming a new furry friend into their home must first come to terms with an unfortunate fact: animals are dirty, like us most of them have lots of hair and are messy. And for a place like the Berkeley Animal Shelter, which sees well over a thousand animals each year, “poop scooping” takes on a whole new meaning.

To get a closer look at the bacterial populations that result from this rapid turnover of animals (who must also reside in relatively dense housing), we swabbed surfaces throughout the shelter. Because most cages and kennels are cleaned daily with a concentrated solution of hydrogen peroxide, we sampled early in the morning, just before the cleaning crew arrived. As a starting point, we swabbed the floors of the cat ward, the dog ward, the office for (human) volunteers and the outside of the building. If all goes as expected, we will see the microbiomes of each animal species well-represented in the samples we’ve taken from their respective surroundings.

In addition, the cats at the facility are housed in one of three areas: one for healthy, adoptable cats that is accessible to the public; one for the feral cats who are awaiting spay/neuter surgery before they are re-released; and one for cats who are sick and need frequent medical attention. We expect that the microbial populations we find at each of these locations will reflect the different statuses of their inhabitants (and perhaps differences in cleaning regimens). We also swabbed the dryer lint filter, the bleach compartment, the handles from each of the sinks, and some intriguing brown crust from a corner of two dishwashers (pictured below).

One subset of these samples that we’re particularly interested in will hopefully reveal some more nuanced differences in the microbiomes of the various feline housing arrangements. In the sheltering world of late, there has been a movement to introduce “two-compartment housing” to catteries. It is thought that this arrangement reduces both the animals’ stress levels and their risk of contracting illness, particularly upper respiratory infections. One of the cat’s compartments holds the food, water, and bed; the other contains only the litterbox. The UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program has designed portals that you can add to retrofit older cage housing in animal shelters.

The shelter that we sampled doesn’t have sufficient space for every cat to have this luxury, but when it was available (n=5), we took a sample from each of the two compartments. We can then compare both of those samples to ones taken from cats who have access to only one compartment.

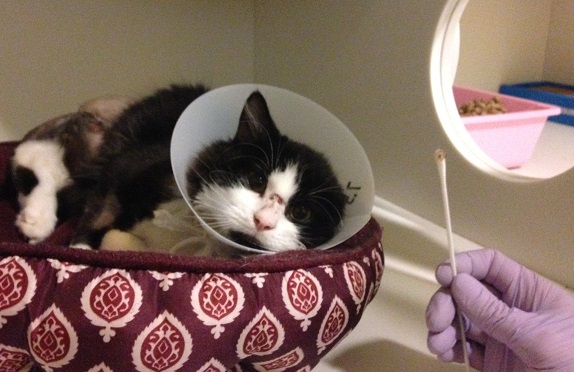

Three-legged Abner the cat was happy to let us sample his room (he is really nice and also available for adoption!). Also visible is the two-compartment arrangement; Abner passes through the circular portal to access the separate space containing his litterbox. I think we all prefer to have our beds separated from our bathrooms.

And so in addition to comparing the clinic housing, feral housing and housing for healthy adoptable cats, we will compare the microbiome of the two-compartment housing, single compartment housing and rooms containing groups of cats who are available for adoption.

I had no idea the two-compartment housing wasn’t standard for cats! I’ve seen it for dogs at every shelter I’ve been to.