See here for Part 1 and here for Part 2 both posted in 2013.

27 April 2014. Leiden, the Netherlands

Holland in April is orange and green. Following last year’s abdication by the Queen, yesterday was the first King’s Day in decades. The normally stoic Dutch draped themselves in brilliant orange, painted temporary flag tattoos on their cheeks, and swaggered and hooted their way through the brick streets, splashing out of bars and filling the streets with moist rubbish. This morning on the train, I am shocked to see beer cans, bottles and cups rolling on the floor among burst chip packets and shredded candy bar wrappers. The country’s railway cleaning staff is on strike.

But the train is quiet as it glides through the green, rainy landscape. Sunday is a family day, perhaps quieter than usual today because of hangovers. Leiden is an old university city, famous for botany and astronomy, and especially for its leading role in the development of western medicine. It was the site of the famous Swammerdam/de Graaf feud, two great friends who became mortal enemies as they raced to unravel the anatomical and cellular basis of human reproduction. The town is also home to the Boerhaave, the Dutch national museum of the history of science. And this museum is home to a few of the ten remaining van Leeuwenhoek microscopes exposed to the public eye. Of the 500 or so he constructed, only ten remain.

My host is Dr. Lesley Robertson, recently retired from the famous Technical University of Delft Department of Microbiology. She enabled my own footsteps on the van Leeuwenhoek trail last year with her booklet on the AvL sites of Delft. Having taken her pursuit of the man she just calls Anthony to new levels now that she no longer has to teach, she graciously agreed to meet me at the museum to look at the microscopes and discuss her transition from scientific to historical research.

The museum was once a cloister, with the foyer and cafeteria now attached to the side like a clam shell. The first exhibit is a replica of a dissection theater, an amphitheater of wooden bleachers surrounding a central table. In such classrooms, professors of anatomy dissected corpses for medical students, and sometimes operated on terrified cats or dogs. Upstairs, in a room filled with glass display cases and reflected light, is a display case not much larger than the one near the van Leeuwenhoek crypt in Delft, but much more interesting.

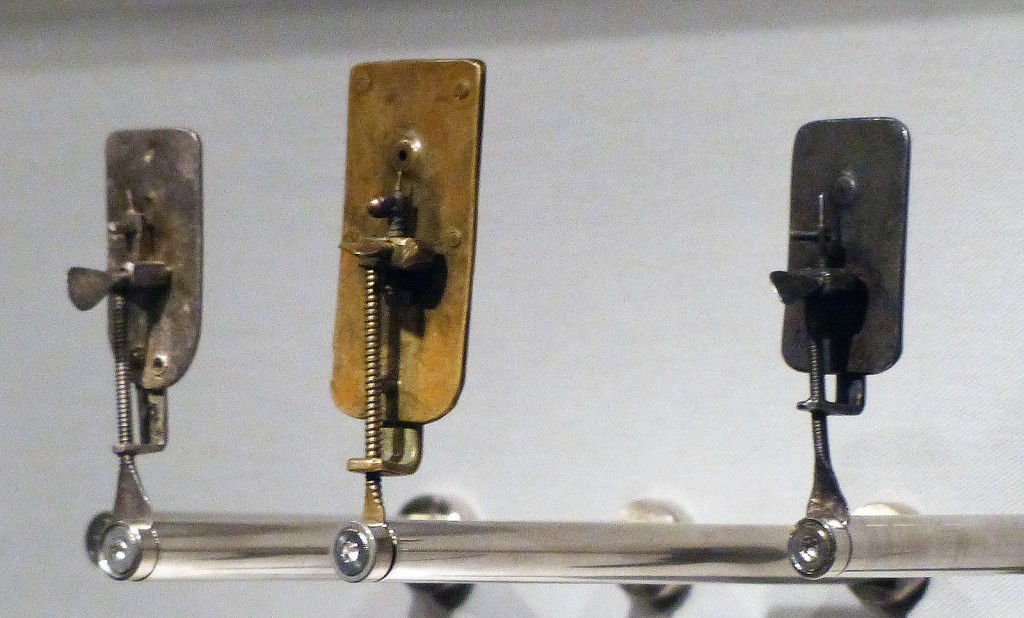

Today, three microscopes are on display. Although I was aware of their dimensions before, they are surprisingly small, about the size of postage stamps. Two thin layers of metal close around the lens, which sits cradled in a bi-convex cavity with a central hole in each side to allow the passage of light. The structure has three sets of screws controlling the three dimensional adjustment of the pin point where the specimen was mounted.

The lenses are the mystery. They were single, globular, and apparently polished using techniques and materials then available for polishing diamonds. In 1654, when van Leeuwenhoek was a young man, an enormous explosion at an gunpowder storage practically destroyed Delft, but scattered so many fragments of glass through the town that there is still a glass stratum in all archeological digs in the city. The shards would have been just lying around on the ground in van Leeuwenhoek’s time and Lesley speculates that Anthony may have used this glass for lenses. Alongside the microscopes is the original contemporary painting of van Leeuwenhoek. He has big hands. It is hard to imagine him manipulating these finicky screws. Lesley says he was a patient man.

The museum is full of other microscopes, including some that elaborated on the single lens lineage before it went extinct, reborn as the famous origami paper microscope late last year. There are several other dead end variations of the single lens theme, based around tubes or boxes, alongside the progenitors of the complex compound microscopes that we use today.

Over pieces of that spectacular Dutch Apple pie (appelgebak, don’t leave the country without trying it),we discuss our mutual interest in van Leeuwenhoek and his technology. Lesley shows me videos on her iPad, taken through her replica microscopes. Her replicas are made by a machinist, a fellow enthusiast as she calls him, who uses glass from jam jars for the lenses. She is excited about her new one that she thinks will give her about 300x magnification, enough to see what most believe are bacteria figured by van Leeuwenhoek. She shows me one with a sample of fossilized Protozoa fixed in front of the lens. After hearing so often now difficult these microscopes are to use, I’m amazed by the clarity of the image. I’m also surprised that you can change the field of view by shifting your eye side to side and up and down.

We page through her new book, compiled in Dutch by her clan of enthusiasts. Lesley is hard-nosed about the need to reconstruct history using scientific standards, emphasizing the importance of concrete evidence rather than the hazy inferences, mistranslations and speculations that seem to contaminate much of the modern retelling of Anthony’s life. Did he know Vermeer? No evidence. Did he give microscopes as a gift to Peter the Great? Sketchy evidence at best, in serious need of corroboration. The inventory of van Leeuwenhoek’s estate was recently unearthed from the Delft archives, and Lesley and her fellow enthusiasts are busily transcribing and translating, documenting the tools and technology that actually were found in his house.

Before leaving the museum, I buy my own replica microscope. Apparently cell phone camera lenses are used for these scopes, and get about 85x magnification. I haven’t decided whether it will be a souvenir or whether to join the optical experimentation.

As we walk back to the train station, Lesley asks what motivates my own quest for van Leeuwenhoek. My answer is to recount a conversation with a journal editor, who told me of her shock when she realized that every paper she edited would become a part of the history of science. We are all part of the history of science. If we are to be part of something, we should make some effort to understand it. My colleague’s epiphany became my own and if microscopy is indeed my aptitude, as I like to believe, then van Leeuwenhoek seemed like a good place to start. But this has been like opening a gate to a castle; there are many rooms to explore on the other side.