As part of the Healthy Buildings 2015 America Conference, there was a technical session on Indoor Microbiome Research where we discussed strategies on, among other things, how to sample and analyze bioaerosols using modern high throughput sequencing techniques. In that workshop, we did a small exercise highlighting the potential for humans to transport microbes into different settings. Prior to the session, one of the panelists (names protected) left the room and handled a fruiting body of a puffball known as Pisolithus tinctorius. Attendees of the workshop were invited to swab those of us on the panel and our possessions in explore if we could later identify which panelist handled the specimen. We used this is a springboard to talk about potential issues in microbiome sampling – spatial variation in microbial communities, do we need duplicate samples, how much pressure to apply and what size area to swab?

The fungal sequences from those dozen swabs from that workshop were pretty clear: the dog turd fungus appeared on swabs from the targeted panelist’s hands, computer, and chair. In fact, it was second most abundant fungus in those samples and not present at all from swabs of other panelists.

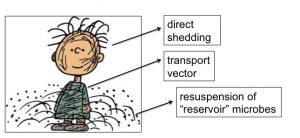

I think about these results in the context of different routes of microbial transmission. Occupants and their activities are a large determinant of the bioaerosols in indoor spaces, and there are thought to be three routes of “occupant emissions”:

- Direct shedding from the human envelope (shedding, spitting, etc)

- Resuspension of microbes that have settled in the indoor environment (“reservoir” microbes)

- A transport vector of microbes collected in other spaces, as in our session

It’s always been a concern in occupational settings for workers not to bring harmful substances on their clothing to the home setting, where in this case it would be workers transporting microbes into their home and creating an opportunity for direct transmission or subsequent resuspension from surfaces in the home.

For a more comprehensive understanding of indoor bioaerosols, it’s important to know the strengths of these three different transmission routes. Teasing apart the relative contributions of these three processes which sum to create a Snoopy-inspired Pig-Pen model of aerosol generation can be challenging.

Some research is tackling this challenge by using environmental chambers. For example, (bio)aerosol particle emissions were approximately 6 times greater when occupants walked around a chamber, compared to when they were sitting. While some of the increased particles were associated increased vigor of upper body movements, most was attributable to release of particles from the floor. In another study, the air in a small chamber with an occupant sitting and wearing minimal clothing can show a unique microbial signature as to identify the individual occupant, showing that direct shedding is detectable when other sources are sufficiently removed. Recently, a study focusing on particles shed from the human envelopment and aiming to minimize resuspsension from the floor linked aerosol release from different activities with personal exposure. For questions about cross-contamination in indoor environments, these kinds of studies can help us better understand the nature of occupant emissions.