Authored by Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg, University of Oregon, Professor of Architecture and Director for the Institute of Health in the Built Environment and Mark Fretz, Research Assistant Professor and Director of Knowledge ExchangeLives & Livelihoods, the UnSeen Hope to Reopen

How are we going to balance decisions about increasing acute risks to human life with chronic risks that come with shuttered economies? This question presents a tenuous balance with high stakes, and forces, a tragic choice between lives and livelihoods. No doubt, if we go #BackToWork too soon, people die. But, #StayAtHome, and livelihoods are threatened, and well, people die. This is not a dramatization. It is a no-win situation that has caused knotted stomach sleepless nights for decision makers at every level of government. It is difficult to reconcile choices to allow some buildings and business sectors to reopen while others remain shuttered. When will it really be safe to reopen our buildings? Not soon enough.

We have exhausted our state of emergency or public health emergency durations, but the state of emergency nonetheless persists. Accordingly, legislative bodies are charting maps through unseen territory forcing interpretations on constitutionality related to matters of public health. Quarantine fatigue has given way to anger played out on social media and in the streets. Public health officials have been drumming “more testing, more testing” for months. The curve has been flattened and in some places is climbing again. How will we solve the elusive riddle to safely reopen the economy? As we walk up to our workplaces the clue is staring us in the face, but we just cannot see it.

Seeing the Unseen

Buildings are the engines of our economy and they make space for our communities to flourish. Buildings are also home to countless microbes (bacteria, fungi, and viruses), including of course, the newest coronavirus. There is a famous restaurant in Guangzhou, China, and a call center in Seoul, South Korea to prove it. Not to mention countless assisted living centers, meat packing facilities, prisons, and even hospitals globally. The notion that COVID-19 spreads inside of buildings should be no surprise, given we spend 90% of our time indoors. We don’t even need to debate primary or secondary routes of transmission or agree about the priority of contract versus droplet or aerosol transmission, nor do we need to use the word airborne, to agree that transmission of COVID-19 in buildings is real. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is in our buildings, because it is in us, and we shed it into buildings when we breathe, cough, sneeze, talk, sing, or, umm, the verb is flatulate. Microbes also come indoors through windows, pipes, pets and mechanical ductwork. Most people have heard about research into the human microbiome, but what about the building microbiome? Indeed, researchers at several universities, including the University of Oregon Biology and Built Environment Center, have been exploring the microbiome of the built environment for over a decade with support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ok, so humans populate the building microbiome, but then what?

Our building microbiome can be thought of as the central nervous system of our constructed infrastructure and it is an important signal with regard to human health. Some microbes indoors are probably good for us, but it is easier to understand a bad actor like coronavirus. Microbes that land on surfaces interact with surface chemicals and thrive or perish. Microbes in the air are pushed around by window or mechanical airflows, and human activities. Enter the novel coronavirus; yes, SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in our buildings.

Monitoring microbes: the vision needed to safely reopen our buildings and our economy

Building monitoring is the clue to solve this riddle. We cannot test every person every day for coronavirus, but we just might be able to test every building every day. This is the evidence that can help guide decision makers about how to most safely reopen the economy. This is the information that will give a hospital engineer confidence that their building air systems are as safe as possible, or knowledge that more extensive mitigation strategies are required. This knowledge will give travelers the confidence to stay in a hotel room or visit a restaurant, and family members with loved ones in assisted living centers the peace of mind they desperately desire. It is the type of data that university administrators can use to guide classroom occupancy decision making and evaluation progressive risk mitigation strategies as campuses open for fall classes. It is also a type of monitoring plan and safety precaution that our most vulnerable populations, and really everyone, deserves. We should be able to walk into a building without fear and anxiety that we may become sick because we entered that building. But it is not that simple.

Shortly after the pandemic struck our shores, the University of Oregon launched a SARS-CoV-2 monitoring campaign focused on critical infrastructure in collaboration with Oregon Health & Sciences University. As important as this is, it is still narrowly focused. Oh, how I wish that widespread building microbial monitoring was already a common practice in December 2019. If it were, we could have quickly retooled our monitoring assays in buildings across the country to search for SARS-CoV-2. Thousands of lives would have been saved and the negative impact on the economy would have been far less severe. Moreover, if we regularly tested building microbiomes, we would be much further ahead than we are now with regard to knowing precisely how to act on these data. When we talk with building administrators about the idea of testing buildings for SARS-CoV-2, we get two reactions. First, astonishment that such a thing is even possible, followed quickly by unease and serious concern about what they may be forced to do with this burden of knowledge or whether there is even anything they can do to reduce or eliminate risks. The good news is there is a range of building design, operations, and disinfection strategies that can be implemented. In fact, our team at the University of Oregon collaborated with researchers at UC Davis and wrote a paper offering guidance to building operators about how to reduce transmission risk indoors. So, to the question, what could we do if we knew we had a sick building, the answers are plentiful. What is required is actionable information to know if you have a sick building, and a layered action plan to deal with intermittent outbreaks. Then, these questions arise. How fast can you monitor your building for SARS-CoV-2 or another novel virus for that matter? Can we do this fast enough to react in a meaningful way? How fast can we implement and scale this up? How much will all this cost? And, wait a minute, we cannot even get enough tests for people, how are we going to test buildings too?

Leverage the infrastructure of public universities

Given the severity of this situation, the confounding and seemingly contradictory behavior of this virus, and the complexity of the interdependencies of the proposed public health strategies, I do not envy federal and state leaders and institutional decision makers for one minute. This is a monstrous dilemma. But there is a great and previously unseen hope.

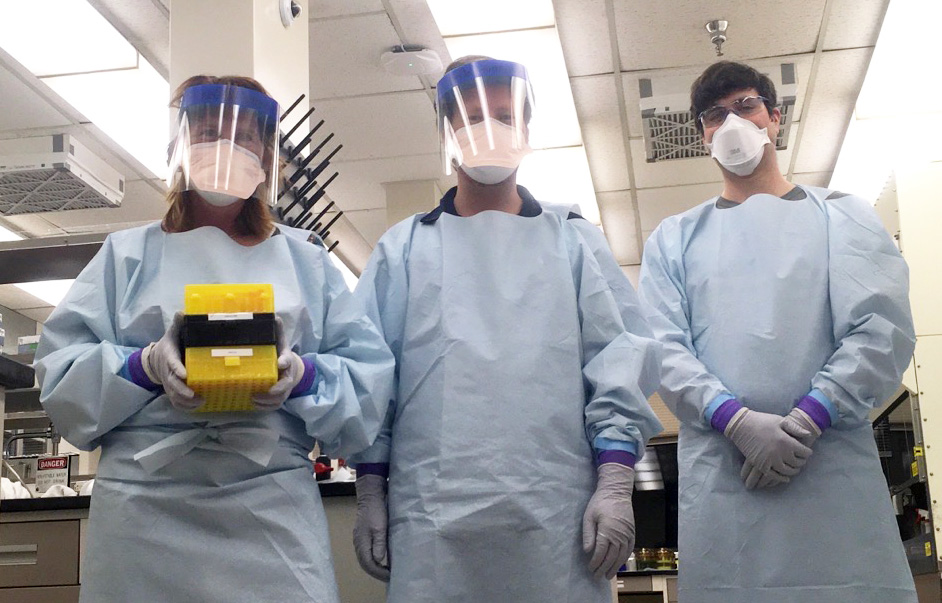

Our team is testing buildings for coronavirus right now. We are working with facility engineers to determine the best strategies to mitigate indoor transmission risk right now. Together, we are conceiving ways to integrate large scale building testing with human testing to comprise more comprehensive contact-tracing programs. We are creating SARS-CoV-2 building reports in a few days, for a modest number of buildings, at a cost of thousands of dollars per report. We need to accelerate this timeline, increase this scale, and slash these costs. To implement this plan, we need to enlist a coalition of those willing to lead and serve their communities. There are thousands of microbiology wet labs currently sitting empty at universities across the globe. Governments are fabricating trillions of dollars in relief in an attempt to treat the symptom and spur economic activity, and while this is important it does not address the root cause. Universities, and private enterprises can team up to treat the cause, and more safely rebuild economic activity in buildings. We have heard from many universities that are willing, even pleading to help. Interest and capabilities are distributed globally and perfectly engaged with the local communities to enact this plan.

We have concepts to achieve building pathogen testing in a near real time fashion through new technology development, at a fraction of the current cost per test. Until then, our current labor-intensive approaches can be economical enough to make an immediate positive impact. As with any product or service, with increased scale comes efficiency and affordability. And therefore, with scale comes equity.

This concept affords individuals a higher degree of personal privacy should they want it, while still notifying others in the same buildings of possible risks of exposure. That is a basic right, just like trusting that you can walk into a building and it will not collapse or be quickly notified if there is a fire so you can safely exit. Testing buildings offers a scale of implementation that is actionable, in the precise location where action is required to create safe spaces. It can bridge the gap in human testing where it is not possible or unwanted. Testing with lower fidelity at the building scale as compared to individual human testing, will allow for an increase in temporal frequency. Technologically, it is possible to rapidly test buildings for pathogens, just like we monitor for fire smoke. In fact, buildings and governments might adopt a Smokey the Bear approach to building safety. We post estimated risks of forest fires, why not post estimated risks of community viral outbreak, since it is impossible to eliminate transmission risk. The question that will remain is, how do we each deal with some degree of risk? If the risk is posted on the door, we will each have access to additional knowledge that we can use to make a personal choice. The key to starting the engine of the economy is to reveal the unseen in buildings. To see the unseen, we must focus on testing buildings.

Friends of MicroBEnet, if you want to help, please reach out or comment!

And perhaps the best way to monitor a building’s condition is not through only sampling of the air, but by also monitoring the Wastewater stream #COVID19 #WBE #DETER

Thanks Michael. I am for both, more info is better. I think the two approaches provide information at different time scales and with different spatial resolutions. Thus, the information is actionable in different ways. I am excited about the built environment transmission risk potential knowledge that can be gained through testing inside buildings. Hopefully stopping or minimizing outbreaks earlier.