A really great read on culturing the uncultured:

I am highlighting a few key parts. First an intriduction to the challenges in culturing with a discussion of work by one of my favorite scientists:

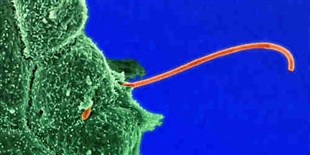

In 2001, Nicole Dubilier, a marine biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, made a surprising discovery–two symbiotic bacterial species living inside a gutless marine worm, Olavius algarvensis. To better understand the unique relationship among the three species, Dubilier set out to culture the two symbionts. But nearly 15 years later, she has yet to successfully grow the bacteria in the lab.

Her best attempt kept the microbes alive for about 10 months, Dubilier says, but then the culture “just died on us. . . . It’s a kamikaze project. How long can you have someone put in all their effort if it’s constantly unsuccessful?”

And then some nice background on culturing:

In 1873, Joseph Lister first introduced serial limiting dilution of bacteria in liquid medium to achieve a pure culture. Then in the 1880s, Nobel laureate Robert Koch invented methods for growing pure bacterial cultures on solid media and his laboratory assistant, Julius Petri, created the round, flat, stackable plate that is still a fixture in microbiology labs. For almost as long, scientists have struggled to cultivate newly identified soil or marine microbes.

And a bit on the “Great Plate Count Anomaly”:

In 1985, microbiologists Allan Konopka of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and James Staley of the University of Washington dubbed this gap between the number of bacterial cells that could be directly counted in an environmental sample and those that could be reproducibly cultivated “The Great Plate Count Anomaly.” 1

And then, well, you should read the whole story – it covers a lot of interesting ground on various attempts to culture more microbes.

Source: A must read if interested in microbial ecology: The Lost Colonies by Anna Azvolinsky